Bill Lofquist and Jody DiPerna

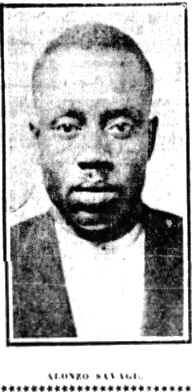

In the fall of 1923, a young woman from Pittsburgh’s East End was murdered. The police built a case against Lorenzo Savage, a young Black man, that closely followed a common, racist criminal justice script of the era. He was portrayed by the police and the media as a brute who was calculating but also impulsive, and who took advantage of Elsie Barthel, an attractive, vulnerable white woman.

The police secured a confession to the murder after a lengthy interrogation, but neither of Barthel’s two white boyfriends — the father of the child she was carrying, nor her fiancé, who was at the scene of the crime that night — were ever seriously considered.

From the first indication that Savage had any contact with Barthel, he was the only suspect. He was tried and convicted within six weeks of Barthel’s death. He was executed just four months later. Savage left behind a family, his wife Regina and his four year-old son, William.

After reassembling and reviewing the available record of the case — the trial transcript, the surviving legal record, and newspaper coverage, and finding any available information on the principal parties — this is an effort to reconstruct the murder of Elsie Barthel, the all-too-brief investigation of the crime, and the conviction and execution of Lorenzo Savage.

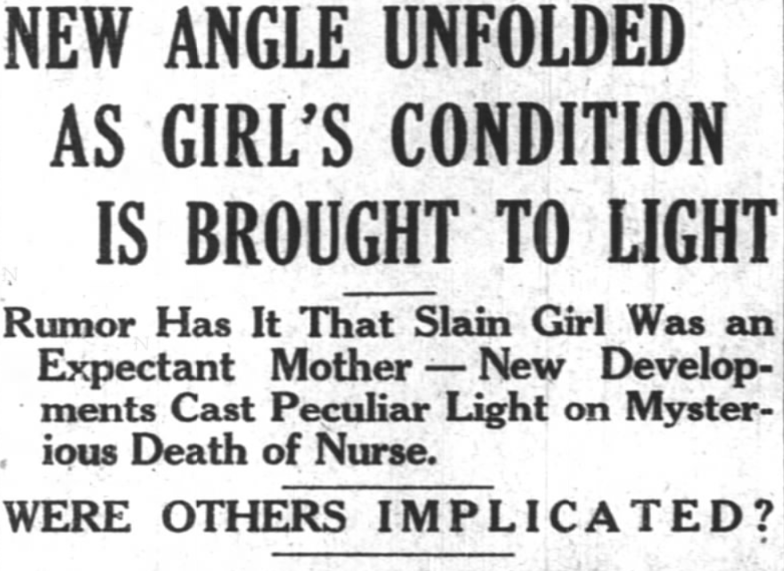

Featured image from the March 25, 1939 edition of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. It is captioned: “The voodoo doctor re-enacted the murder he had committed.”

***

The Death of Elsie Barthel, October 6, 1923

In the fall of 1923, Elsie Barbara Barthel was a 28 year old, single woman who lived with her family in Bloomfield and worked as a nurse in Shadyside. She was also pregnant. Her fiancé, Walter Haule, was not the father of her child and probably did not know she was expecting. She did not want to marry Haule. Instead, she wanted to marry John Roger Daugherty, the baby’s father. With her pregnancy becoming visible at 18 weeks, the need to break things off with Haule was urgent.

She arranged to meet Haule that Saturday evening, October 6, 1923, at the Hussey Mansion, an abandoned building at the corner of Center and Cypress Avenues (now part of the grounds of Shadyside Hospital). It was a place sometimes used for romantic meetings for unmarried couples.

She also arranged to meet with a former co-worker, Lorenzo Savage, at the same spot before she met with Haule. Savage later testified that Barthel told him that she used this spot as a “trysting place,” according to the Pittsburgh Post (one year later, it would be the Post-Gazette) reports during the trial. He also testified that she wanted him to use magical powers she imagined him to have in order to help lay the path to her marriage with Daugherty. Because of religious differences — Daugherty was Irish-Catholic while Barthel was Lutheran — their marriage was unlikely.

Growing up in a city with a storied Black community, Barthel was attracted by the allure of Black culture, both real and fanciful. She accepted widely-held racist beliefs about Black supernatural powers and the occult, and thinking, or maybe just hoping, Savage might possess such powers, she pressed him for weeks to use playing cards to help, “cure her of a trouble … due to a love affair,” as the Pittsburgh Press delicately described it at the time. What does seem likely is that Barthel set up this meeting with Savage in the hopes that he could help her bring to pass her marriage to Daugherty.

There is no evidence that Savage was a practitioner of voodoo or any magical art. His only credential in this realm seems to be race. Whether or not he helped foster Barthel’s belief in his occult abilities, or reluctantly played along by indulging her hopes in this regard, he did agree to meet and bring the cards she requested. They met briefly. He gave her some playing cards and she paid him approximately $30, according to testimony provided by both the police and Savage himself.

Savage also testified that after he met Barthel, he headed to a dance at East Liberty’s Arcade Hall on foot, unaware of the meeting to happen between Barthel and Haule. While walking to Arcade Hall, he remembered plans he made to go to a friend’s house on Bedford Avenue in the Hill District. Rather than double back, he got in a taxi at the intersection of Highland and Penn Avenues. It was 9:45 pm. That cab was driven by Walter Haule, Barthel’s fiancé.

The next morning, Laura Barthel, Elsie’s younger sister, awoke at the family home and found Elsie was not home. She checked two local hospitals before going to the office of Elsie’s employer, Dr. Robert S. Marshall. The two went to the Homeopathic Hospital (now Shadyside Hospital.) They turned up no leads on Elsie, and Laura returned home.

Around the time Laura left, a local resident was walking through the Hussey property and found Elsie’s body. He asked someone to notify the police while he alerted doctors at the hospital next door. Marshall wondered if it was Elsie — he went out and found the body of his secretary.

The police arrived and found playing cards under Barthel. Envelopes and a handkerchief were nearby.

Barthel’s body was taken to the coroner’s office, where it was identified by Daugherty, the father of the child Barthel had been carrying. It is not clear who notified him or why he was notified rather than Barthel’s mother or sisters.

Building a Case Against Lorenzo Savage

Laura Barthel told the police her sister Elsie planned to meet her fiancé Haule on Saturday evening. She also told the police that her sister spoke on the telephone with Savage earlier that day and arranged to meet him. Elsie’s mother, Margaret Barthel, testified that she heard Elsie speaking on the phone with Savage and that her daughter left their home at 8:30 that evening.

The police questioned Haule and learned that he picked up Savage in his taxi that night. He told police he previously met Savage at Dr. Marshall’s office, but he didn’t recognize him when he picked him up that night. Haule’s presence so near the murder was odd, police thought, but Haule assured them it was just the nature of driving a cab. Haule’s boss backed him up.

Haule also told the police that Savage, “would not have lived to be arrested,” had he known what happened to Elsie, according to the Post. After briefly considering Haule a suspect, the police came to view him as a witness instead. They were likewise untroubled by Daugherty’s relationship to Barthel and any questions that may have raised.

They focused their investigation on Savage.

The police searched Savage’s room in C.S. Mitchell’s Shadyside home and found playing cards, the design of which matched those found at the murder scene. They arrested Savage late Sunday afternoon. He had $25 on him.

When the police looked in Barthel’s room in her family home, they found nearly $400.

The police put together a theory that Barthel was to pay Savage $400 and that the evening turned violent when she reneged on paying $400 and offered him $31 instead. They further theorized that after Savage gave her some playing cards, she then grabbed back her money. Incensed by this, Savage struck her with his fist and knocked her down, then struck her with a brick. Finally, he killed her by pushing a 75 pound chunk of granite from the mansion’s crumbling portico onto her head.

[Although it is hard to follow the reasoning about the money here, the police theory seems to be based on the money found in each respective room — the $400 Elsie had saved and the $25 Savage had on him, taking into account the money he is alleged to have spent before he was arrested.]

Savage was questioned for 10 hours without a break. After this long stretch of non-stop questioning by a rotating cast of officers, Savage confessed to this version of events. It was now 2:30 in the morning on Monday, October 8, 1923, approximately 29 hours since Barthel and Savage met at the Hussey Mansion.

The police said Savage’s confession was secured voluntarily, “without a raised voice or hand.”

Coercive investigative tactics were so common in this era that a reorganization of the Pittsburgh police was undertaken in 1922. The new chief of detectives ordered “radical changes” to police methods, including an order by the Superintendent of Police that would eliminate “all third-degree” techniques commonly employed by police, as reported by the Post.

But reports of alleged use of coercive tactics continued unabated. The Post reported on November 17, 1923, that a bill was proposed for inquiry into oversight of the police; the probe would bring to light the use of use of police brutality in modern policing, saying, “Defenders of the third degree sweating of suspects, which is becoming common, contend it is necessary to assure efficiency in the apprehension of criminals, however, without denying that the methods employed often border on torture.”

John Hickey, who led the questioning of Savage and ultimately elicited his confession, was among those implicated in the use of such tactics and was charged, and exonerated, of having subjected a suspect to a “violent third-degree” according to the Pittsburgh Post on June 1, 1923.

Around 3:00 am, the police took Savage to the crime scene and had him ‘re-enact’ the murder for them — where he was standing, picking up a brick, pushing a heavy chunk of granite. He was then taken to the jail on Ross Street, downtown. Near noon, the police took him back to the Hussey Mansion where they had him again ‘re-enact’ the crime — this time for newspaper photographers and reporters the police had assembled, as well as dozens of curious onlookers.

The Sunday morning newspapers had already hit the streets before Elsie’s body was found, but when the papers went to press on Monday, the Barthel murder led the coverage in both the Pittsburgh Post in the morning and the Pittsburgh Press in the afternoon.

The Pressure to Convict

Making a case against Lorenzo Savage was not hard. The Pittsburgh police were anxious to avoid any opprobrium for not solving the murder of a white woman, a murder that would certainly grab headlines, particularly in this climate. A Black man near the scene of the crime provided a clear target.

This was an era during which the Ku Klux Klan was resurgent and emboldened, not just in the south, but in northern cities, too. Six weeks before Barthel’s murder, the KKK rallied in Carnegie, a municipality seven miles from downtown PIttsburgh. Thousands attended and there were violent confrontations between the Klan and local opponents, resulting in one death.

“Pennsylvania had the second most Klan members in the country, after Indiana, in the 1920s,” said Rob Ruck, historian and professor at the University of Pittsburgh. Ruck is the author of several books about Pittsburgh, his most recent is Pittsburgh Rising: From Frontier Town to Steel City (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2023.) According to Ruck, this era is one of great upheaval and disquiet in Pittsburgh and in the United States more broadly; in the north in particular, the Klan was equal parts racist, antisemitic and anti-immigration.

Elsie Barthel’s death came just four years after the Red Summer, which stretched from late-winter to late-summer of 1919. During that time, Black citizens and communities were targeted by white citizens causing hundreds of Black people to be injured or killed, according to the Equal Justice Initiative. There were large-scale racist attacks across the country. In 2019, the hundred year anniversary of the Red Summer, PBS reported that researchers believe more than 250 African Americans were killed in at least 25 riots across the U.S. by white mobs over a period of 10 months. Those white mobs never faced punishment.

“The red summer of 1919, and you’ve also got a labor upsurge at the end of the war, which included perhaps the largest walkout ever in US labor history — that of the steel workers,” Ruck explained.

“In a city like Pittsburgh, immigration from southern central and eastern Europe and migration from the Black south are very unsettling to people. That I think is pretty much larger context.”

In the north, particularly in an industrial city like Pittsburgh, this is a time of fearfulness for many white Americans.

“One word that comes to me about this time is anxiety,” Ruck said. “Despite prosperity and upward mobility, there’s a lot of anxiety — about race, about immigration and about gender.”

The media was likewise eager for a villain. From the moment he was arrested, Savage was dubbed by police and newspapers as the “voodoo doctor” or “voodoo man.” This was a common narrative at the time — born in the racist imaginings of the police and spread through white newspapers.

H. B. Laufman, a Pittsburgh based reporter for the Wall Street Journal and New York Post wrote a particularly overwrought story for the Toronto Star in which he led with this description: “Beating on his steel bars a fantastic rythm (sic) reminiscent of the booming ‘drum talk’ of the cane brakes of Jamaica, “Doctor” Lorenzo Savage, negro high priest of Voodoo, crouches on the stone floor of his cell in the Allegheny county jail awaiting trial for the murder of pretty Elsie Barthels (sic) …”

[It should be noted that Laufman was well thought of and influential in the Pittsburgh media landscape. According to his obituary in the Pittsburgh Press in 1964, he held “every post in the Pittsburgh Press Club,” through his career; he was president of the club in 1908 and vice-president in 1911, 1919, and 1920, per newspaper reports of the era.]

Though Laufman’s story was exceptionally histrionic, he wasn’t alone in using the voodoo depiction to lure readers. In addition to the local market, stories appeared in papers across the country from the New York Times to small-town Montana; as far away as Melbourne, Australia, the Sun-News Pictorial ran a story titled, “Girl Killed by Voodoo Man.”

Specters of racial and sexual intrigue, supernatural powers, and violent death loomed. Voodoo was often used in reference to Black defendants at the time, even as those claims were often unsupported and fabricated.

“Jim Crow was not only a system of the South, but it was a national system,” said Kathy Roberts Forde, journalist and journalism historian at UMass Amherst.

“Of course, the US news media were highly segregated at the time, and the white news media had certain practices and norms that were profoundly white supremacist and racist. They hid under the claims of objectivity and disinterestedness and neutrality, even as they were engaging in this highly profitable reporting which demonized Black Americans and particularly Black men.”

Less dramatically, Savage was the eldest of the four children born to John and Annie White Savage, who were both born in the confederate state of Virginia as slavery was ending. His family moved to New Jersey where he grew up and married. He and his wife Regina moved to Pittsburgh in 1919 and together they worked in the homes of various affluent East End families. He turned 25 years old just 10 days after his arrest and he and Regina had a four year old son, William.

Pittsburgh, of course, had the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the most important Black newspapers in the nation, along with the Chicago Defender. The Courier would later become a powerhouse paper, but in 1923, there were still very tight financial margins. The Courier also published weekly, so their ability to cover such a fast moving case was limited by their printing and distribution schedule. Not so for the white daily papers in Pittsburgh, the Post and the Press.

The Pittsburgh Courier was the only paper that didn’t refer to Savage as a voodoo doctor, writing as follows:

“The ‘voodoo’ charge was developed when it was learned that Miss Bartell (sic) had such faith in Savage’s ability to play whist and other card games that she thought by some strange manipulation he could influence her case with them.” (Pittsburgh Courier, November 24, 1923.)

Police said they solved the “voodoo murder” case just hours after finding Elsie Barthel’s body. There were no witnesses, no forensic evidence (even by the standards of the day), and the evidence of Savage’s guilt was his confession.

“Of course, this kind of crime has always sold — it always made newspapers and news media profitable,” said Roberts Forde. “When it comes to the way white news media have covered the Black America … it’s been highly sensational, and it’s been part of the profit motive.”

Roberts Forde says that research of the news media, legacy white news media in particular, shows that the media has helped build a racist criminal justice system.

“They’ve been collaborators in building these systems,” she said.

The Trial, November 18, 1923

The trial was scheduled to begin on November 18, 1923, a date the Post declared, “set a record for speedy justice.”

Rising young Black attorney William H. Stanton was appointed as Savage’s counsel just a week before the trial. Stanton was a skilled lawyer, but a week was hardly enough time to prepare a defense that might balance the scales of justice in such a hostile climate.

“Sometimes you have counsel in name only because they don’t really have the time to actually prepare — that sounds like what probably happened here,” said Sara Mayeux, a legal historian of the twentieth-century United States and associate professor of both law and history at Vanderbilt University. She has written extensively on criminal law and procedure, constitutional law and legal culture and is the author of Free Justice: A History of the Public Defender in Twentieth-Century America (UNC Press, 2020.)

It wasn’t until after the 1963 Supreme Court decision in the case of Gideon v Wainwright that the state was required to provide defense counsel to impoverished defendants. In the majority opinion, Justice Hugo Black wrote, “The right of one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials in some countries, but it is in ours. … This noble ideal cannot be realized if the poor man charged with crime has to face his accusers without a lawyer to assist him.”

For Lorenzo Savage, tried forty years before Gideon, the constitutional right to counsel, “[w]ould have been very limited. If it existed at all, it would have mainly been a question of state law,” according to Mayeux. Allegheny County relied on an assigned counsel system, in which attorneys were appointed to represent indigent clients at the discretion of the court and paid a modest, fixed rate. Attorney Stanton was very likely appointed to Savage through this system.

For the state, three attorneys worked the trial to present the case against Savage as described by the police. Their theory of the case was that Savage met Barthel and they argued over money. In a rage over her deception, he bludgeoned her to death and he then confessed voluntarily.

In one of the more difficult to follow elements of the state’s case, police asserted that Savage originally asked for the kingly sum of $395 (the equivalent of more than $7,000 today) for the voodoo fix. In reading newspaper accounts of the day and the testimony at trial of various police officers, it’s hard to trace how police came up with this figure, but what does seem possible is that the $400 police found when they searched Elsie’s room (money she had saved while working and living at home) became, in their minds, money she intended to pay Savage.

The Courier reported that Savage testified that he told Barthel that he couldn’t do it, i.e, work some voodoo for her, but he eventually agreed to give her the cards for money, and Barthel suggested the payment amount — it was not a recompense that he demanded.

On the witness stand, Savage repudiated his confession and his defense attorney argued his client’s confession was coerced. Savage testified that he was handcuffed and forced to stand and was “pounded in the stomach,” until he confessed.

Police officer John Hickey led the questioning. Savage testified that Hickey had threatened to “mash his brains out,” unless he confessed. Hickey was one of the officers implicated in several of the cases of officers known to use the “third-degree,” in newspaper reporting in 1922 and 1923.

Stanton argued that not only was his client’s confession coerced, but that the state did not seriously pursue Haule (Barthel’s fiancé) or any other potential suspects. There are multiple references to Barthel’s sweetheart and that didn’t mean Haule, but someone else. Often the object of her affection was referred to as Rodger (John Daugherty’s middle name) and it is important to reiterate that the police called in Daugherty to identify Barthel when her body was taken to the coroner’s office, rather than her parents or one of her sisters.

Stanton acknowledged that Savage met with Barthel, but had done so reluctantly, at her urging, without making any promises. He said Savage left that meeting and went on his way and that Haule was very close by.

Stanton also called a witness who told the police she had seen a car with two men and that she heard a woman screaming late the previous evening, the night of Barthel’s murder. Minerva Roussar, a dietician at the hospital, said she heard a woman scream, “For God’s sake, don’t!” a full hour after police claimed Savage had committed the murder. Stanton opined that police did not follow this potential lead in their investigation.

After a two-day trial concluding on November 21, the assembled crowd expected a quick conviction. When deliberations continued into the next day, rumors circulated that the jury was split, but Savage was convicted on November 22.

Twelve white men made up the jury. Women got the right to vote in the United States just three years prior to this homicide. In many states, suffrage meant eligibility for jury duty, which was the case in Pennsylvania where registered women voters became part of the potential jury pool right away. (Not so in every state. Mississippi was the last state to permit women to serve on juries in the summer of 1968.)

Though women were eligible to serve on juries, they were not to serve on this trial, as the Press reported “Women jurors were excused …” on November 19, 1923. That said, the Post-Gazette reported that the courtroom was packed with women who came to watch the trial.

White prosecutors and police presented a story of a Black man with primitive magical powers killing a young white woman to an all-white male jury, all chronicled by a pliant white media. The case was built exclusively on circumstantial evidence and a repudiated confession. There was no corroborating evidence of Savage’s alleged magical powers. The defense attorney had just days to prepare and no resources to represent Savage after trial.

Once convicted and without money to pursue an appeal or clemency, Savage moved through the system from conviction to execution faster than any Pittsburgh defendant since 1866. There were three cases in 1866 that moved through the system faster than Savage’s case — Martha Grinder, who was executed on January 19, 1866 and the case of August Frecke and Benjamin Marschall, executed on January 12, 1866.

No appeals were filed for Lorenzo Savage. There was no court or other legal intervention on his behalf. On March 30, the Post-Gazette reported that there was an effort by Savage’s friends to raise enough money to file an appeal to the pardon board, but they were unable to raise the means, writing, “Savage saw his last hope fade when his friends failed to collect the funds.”

Savage was held in the Allegheny County Jail from the night of his arrest in October 1923 until March 28, 1924, when he was transferred to Rockview Penitentiary.

On Monday, March 31, 1924, Lorenzo Savage was executed by electric chair at Rockview Penitentiary in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania.

The following day, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported: “Lorenzo Savage, Negro ‘voodoo doctor’ of Pittsburgh, convicted murderer of Elsie Barthel, was electrocuted at the penitentiary today. Savage went to his death calmly. He made no statement as he was taken to the chair at 7:10 a.m.”

The Pittsburgh Courier highlighted the fact that Savage maintained his innocence until the end. In a story headlined, “Savage Pays Penalty with Smile on Lips” in the April 5, 1924 edition, they included Savage’s pronouncement of innocence:

“‘I am innocent and I face the future with a clear conscience.’

“These were the last words spoken in Pittsburgh by Lorenzo Savage, who died in the electric chair Monday, for the death of Elsie Barthel, white nurse. The words were spoken to Warden Edward Lewis.”

Postscript

Lorenzo Savage is buried in the Prison Cemetery at Bellefonte in Centre County, Pa. His wife, Regina, never remarried. She died in February 1964 in the home she shared with her son William, Lorenzo’s only child, on Catherine Street in Philadelphia. She was 63 years old at the time.

Elsie Barthel’s father died when she was a child. She was mourned by her mother, Margaret (Zenkel) Barthel, as well as her sisters, Laura, Alvina and Anna. She is buried at Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

John Roger Daugherty, father to Barthel’s child, was a devout Catholic. He lived with his widowed mother until he married an Irish woman when he was 47 years old. He was the only one of his siblings to marry.

Walter Haule, Barthel’s fiancé, married sometime in the few years after Barthel’s murder, but by 1940, he was institutionalized and diagnosed with psychosis caused by untreated syphilis. After release, he lived for at least a decade in a group home operated by the Pittsburgh Association for the Improvement of the Poor.

***

Author’s Note: Bill Lofquist begin by laying out the case as it unfolded on the ground, in the newspaper, and in court. After having done so, he returned to that timeline with an alternative theory of the case derived from information not available or used in court, a contemporary lens on the racial dynamics of the era, and an understanding of the racial dynamics of wrongful convictions.

Author Bio: Bill Lofquist is a Pittsburgh native and Professor at the State University of New York at Geneseo. His work on the history of the death penalty in Allegheny County may be found at state-killings-in-the-steel-city.org. All questions and comments are welcomed at lofquist@geneseo.edu